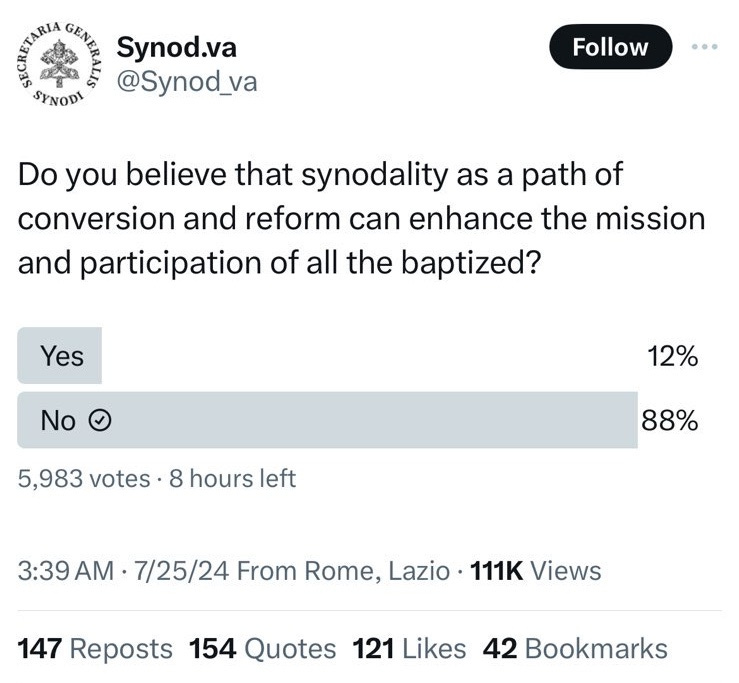

Polls, as a rule of thumb, should be taken with a grain of salt. Or even, at times, with a salt shaker. That said, the recent online poll by @Synod.va—the official X (formerly Twitter) account of the Secretariat of the Synod—was surprising. When I took a screen shot of it on the afternoon of Friday, July 26, nearly 6,000 votes had been cast. And they were overwhelmingly negative—to the tune of 88% voting “No” to the following statement: “Do you believe that synodality as a path of conversion and reform can enhance the mission and participation of all the baptized?”

Not long afterwards, after some 7,000 votes had been registered, the poll was removed.

A couple of days later, I was on the phone with a priest who had worked in the Vatican for several years and is now the pastor of a large parish in a large U.S. city. “No one really cares about it,” he said when I asked what his parishioners think about synodality. “Nobody really knows what it means,” he said, “and it has little or no bearing on their daily lives as Catholics.” Again, polls should come with salt and anecdotes are limited. But synodality—the Pope Francis, current Vatican version of it—seems to hold little interest for many Catholics.

The New Synodality

Part of the problem is, I think, simple enough: if you’re going to claim that Product Z is a new and improved version of Product A, you’d better be able to explain what it is, how it works, and why it is better. And why it is necessary.

In my April 18, 2023 essay on this site, titled “Ambiguity and Clarity in the Age of Synodality,” I noted that the meaning of “synodality” is important “for many reasons, not least that we’ve been living in a ‘synodal Church’ since sometime in October 2015.” That was when Pope Francis, at a commemoration of the fiftieth anniversary of Pope Paul VI instituting the synod of bishops, stated:

A synodal Church is a Church which listens, which realizes that listening “is more than simply hearing”. It is a mutual listening in which everyone has something to learn. The faithful people, the college of bishops, the Bishop of Rome: all listening to each other, and all listening to the Holy Spirit, the “Spirit of truth” (Jn 14:17), in order to know what he “says to the Churches” (Rev 2:7).

Synods, of course, go back to the early centuries of the Church. But the idea of a “synodal Church” is, again, very new. Also new is the quickly expanding lexicon used to explain that concept, including “synodal process,” “synodal listening,” “synodal conversion,” “synodal path,” “synodal journey,” “synodal life,” “synodal method,” “synodal perspective,” “synodal practice”—well, you get the synodal idea.

And yet, oddly enough, the synodal flood of synodal adjectives, rather than shedding light, appears to have mostly bewildered, befuddled, confused, or annoyed many Catholics (at least, those who have paid attention). Ironically, while “listening” (or “synodal listening”) plays a major role in the synodal process, one has to wonder how many are listening.

The 2024 Working Document

On July 9th, the “Instrumentum laboris” for the Second Session of the 16th Ordinary General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops (October 2024) was released. It will be the document discussed for four weeks this fall, focusing on “how to be a missionary synodal Church.”

Some context: back in January 2023, I wrote a critical piece on the Working Document for the Continental Stage (DCS) of the 2023 Synod on Synodality, describing it as “the most incoherent document ever sent out from Rome.” In April 2023, I wrote an essay about how even those touting and lauding synodality seemed unable to really explain it. Then, in October 2023, I penned a critical essay about the Instrumentum laboris for the 2023 Synodal gathering in Rome, stating:

It is difficult, frankly, to see the current synodal documents as anything other than third-rate, flawed texts that water down or ignore completely central aspects of ecclesiology, soteriology, and eschatology, as found in Sacred Scripture and Tradition in general or in the Vatican II documents specifically. If the Synod is to lead to a deeper understanding of the Church, her role in salvation, and her desire to expand the Kingdom of God, it will have to free itself from the bureaucratic brambles and laborious drivel that dominate its documents.

And in December 2023, I opined on the Summary Report from the October 2023 meeting, again noting the struggle to define synodality and to explain why a “synodal Church” is suddenly needed after 2000 years. It was evident that “experience” was a key word and emphasis from the start, and one that continued in the December report:

... it's not surprising that “experience(s)” appears almost 80 times in the synthesis report, and that the favored term “discern(ment/ing”) is used 38 times. Which is quite a few more times than words such as “teaching” (18), “truth” (8), “doctrine” (6), or “dogma” (0). Experience certainly has its rightful place, and proper discernment is a good thing, but there are questions aplenty about the basis for making proper judgments and decisions.

So, is this new Working Document an improvement over previous documents? The short answer is, “Yes, but…” The longer answer is, first, that it didn’t take much to improve on the earlier documents and, second, with some modest exceptions, the improvements are quite minor. It’s the sort of improvement you see when your operating system goes from 9.3.1 to 9.3.4. And there are still plenty of bugs.

A Thousand Words Is Worth a Synodal Picture

Like previous synodal documents, this one is fairly long at over 20,000 words. And, as expected, the same words and jargon show up on a regular basis. The words “process/es” (60), “experience” (32), “dialogue” (30), and journey/ing (35) appear often. “Listen/ing” (48) is, of course, quite popular, while “hear/ing” (1) is not. There is substantial focus on “discern/ment” (61), “service” (38), with “unity” (89) and “communion” (148) appearing very often.

Three “c” words crop up several times: “context” (50), “concrete” (31), and “culture/cultural” (43). And so we find passages such as this:

As it exists in service to mission, synodality should not be thought of as an organisational expedient but lived and cultivated as the way the disciples of Jesus weave relationships in solidarity, capable of corresponding to the divine love that continually reaches them and that they are called to bear witness to in the concrete contexts in which they live. Understanding how to be a synodal Church in mission thus passes through a relational conversion, which reorients the priorities and the action of each person, especially of those whose task it is to animate relationships in the service of unity, in the concreteness of an exchange of gifts that liberates and enriches all.

There’s surely some good stuff in there, but the synodal process seems to have buried it!

The emphasis on “witness” (14), “mission” (44) and “missionary” (37), is heartening, although it is strange that “evangelize/evangelization” (5) are rarely used. One of the better passages hones in on the Trinitarian nature of missionary work and proclaiming the Gospel:

“The pilgrim Church is missionary by her very nature, since it is from the mission of the Son and the mission of the Holy Spirit that she draws her origin, in accordance with the decree of God the Father” (AG 2). The encounter with Jesus, the adherence in faith to his person, and the celebration of the sacraments of Christian initiation lead us into the very life of the Trinity. Through the gift of the Holy Spirit, the Lord Jesus enables those who receive Baptism to participate in his relationship with the Father. The Spirit with whom Jesus was filled and who led him (Lk 4:1), who anointed him and sent him out to proclaim the Gospel (Lk 4:18), who raised him from the dead (Rom 8:11) is the same Spirit who now anoints the members of the People of God. This Spirit makes us children and heirs of God, and it is through the Spirit that we cry out to God, calling him “Abbà! Father!”.

To understand the nature of a synodal Church in mission, it is indispensable to grasp this Trinitarian foundation, and in particular, the inextricable link between the work of Christ and the work of the Holy Spirit in human history and the Church: “It is the Holy Spirit, dwelling in those who believe and filling and ruling over the Church as a whole, who brings about that wonderful communion of the faithful. He brings them all into intimate union with Christ, so that he is the principle of the Church’s unity” (UR 2). (#22–23)

However, this demonstrates a characteristic evident throughout this document and previous documents: the forced quality of using “synodal” to describe realities that have been a part of the Church since her founding. Again and again, various activities—witnessing, discerning, listening, caring for the poor, showing respect for women—are treated as though they are somehow new, previously undiscovered and not practiced. At risk of dating myself (yes, I was in high school in the 1980s), it reminds me of the massive 1984 campaign for “new Coke,” which resulted in consumers essentially saying, “Naw, we don’t like it. We want the real Coke.”

Doctrinal Disconnect

Further, while a handful of theological passages are good to see, they also have a forced quality to them, precisely because they don’t inform or suffuse the majority of the document. I suspect that some of this is due to the nature of texts-by-committee, but I also think it reflects a deeper problem. Namely, that there isn’t much interest in emphasizing the dogmatic, doctrinal, and confessional qualities of being a Catholic and what that means for the Church as the Body of Christ (mentioned seven times, while “People of God” appears almost 50 times). While there is much emphasis on personal charisms (26 mentions), divine revelation (1), doctrine (1), dogma (0), deposit of faith (0), “teaching” (2), and “catechesis” (2) are given short shrift. Experience, again, is in heavy rotation.

And, as in previous documents, the fuller nature of redemption and salvation does not come into focus. In fact, “salvation” and “sin” are never mentioned; “redeemed” appears once. Virtue is never mentioned and “holiness” comes up just twice. Once again, the eschatological character of faith and of the Church is pushed to the fringes, if not buried altogether.

Finally, it’s troubling that a document about the Church and her mission never quotes any words of Jesus Christ or, really, anything at all from the Gospels. The sense of detachment, overall, is curious. Granted, this is a working document and I suspect very few of the 7,000 people who voted in the aforementioned poll have read it. But passages such as this one (many others would have also sufficed) suggest the detachment and the disdain of many for things synodal:

A synodal Church is a relational Church in which interpersonal dynamics form the fabric of the life of a mission-oriented community, whose life unfolds within increasingly complex contexts. The approach proposed here does not separate but grasps the links between experiences, allowing us to learn from reality, which is reread in the light of the Word of God, from Tradition, from prophetic witnesses, and also reflects on mistakes made.

Further, many Catholics aren’t interested in documents that talk a lot about “transparency” (15) and “accountability” (19) when men such as Fr. Marko Rupnik continue to apparently enjoy the favor of Pope Francis. Mistakes are made, of course, but some mistakes are far more troubling than others, especially when they happen repeatedly.

“The synodal conversion of minds and hearts,” the Working Document states, “must be accompanied by a synodal reform of ecclesial realities, called to be roads on which to journey together.” Well, okay. Or, as the first pope said at Pentecost, in proclaiming the Gospel to those present:

And Peter said to them, “Repent, and be baptized every one of you in the name of Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of your sins; and you shall receive the gift of the Holy Spirit. For the promise is to you and to your children and to all that are far off, every one whom the Lord our God calls to him.” And he testified with many other words and exhorted them, saying, “Save yourselves from this crooked generation.” (Acts 2:38–40)

Carl E. Olson is editor of Catholic World Report and Ignatius Insight. He is the author of Did Jesus Really Rise from the Dead?, Will Catholics Be “Left Behind”?, co-editor/contributor to Called To Be the Children of God, and author of the “Catholicism” and “Priest Prophet King” Study Guides for Bishop Robert Barron’s Word on Fire. His recent books on Lent and Advent—Praying the Our Father in Lent and Prepare the Way of the Lord—are published by Catholic Truth Society. Follow him on Twitter @carleolson.

Listen to or watch Carl discuss this article with Larry Chapp.