The Role of Canon Law

In the period immediately preceding the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council and, even more so, in the post-Conciliar period, the Church’s canonical discipline was called into question at its very foundations. The crisis of canon law had its origin in the same philosophical presuppositions which were inspiring a moral and cultural revolution in which the natural law, the moral ethos of individual life and life in society, was questioned in favor of an historical approach in which the nature of man and nature itself no longer enjoyed any substantial identity but only a changing, and sometimes naively-considered progressive, identity.

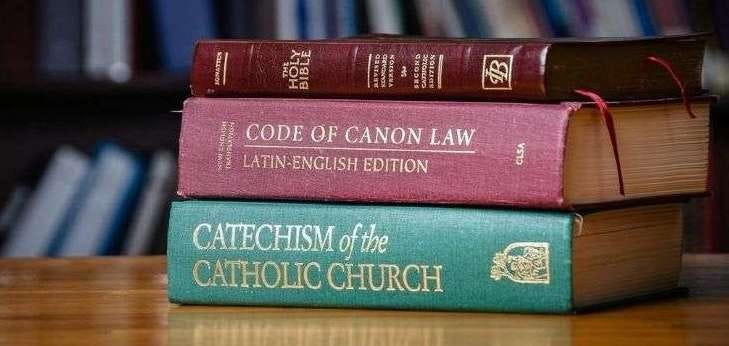

Within the Church, the reform of the 1917 Code of Canon Law, announced by Pope Saint John XXIII, a reform which did not begin in earnest until some 10 years later and then slowly progressed during the last years of the Pontificate of Pope Saint Paul VI and the first years of the Pontificate of Pope Saint John Paul II, seemed to question the need of canonical discipline and opened a forum for certain theologians and canonists to question the very foundations of law in the Church. The so-called “Spirit of Vatican II,” which was a political movement divorced from the perennial teaching and discipline of the Church, exacerbated the situation greatly. After a period of intense labors and heated discussions, Pope Saint John Paul II promulgated the revised Code of Canon Law on January 25, 1983, some twenty-four years after it had been announced.

During the lengthy pontificate of Pope Saint John Paul II, great progress was made in renewing the respect for canonical discipline which, as he explained in promulgating the 1983 Code, has its earliest roots in the outpouring of the Holy Spirit into the hearts of men from the glorious pierced Heart of Jesus.1

In promulgating the Code of Canon Law, Pope John Paul II recalled the essential service of canonical discipline to the holiness of life, the renewed life in Christ, which the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council wished to foster. He wrote:

I must recognize that this Code derives from one and the same intention, the renewal of Christian living. From such an intention, in fact, the entire work of the council drew its norms and its direction.2

These words point to the essential service of canon law in the work of a new evangelization, that is, the living of our life in Christ with the engagement and energy of the first disciples. Canonical discipline is directed to the pursuit, at all times, of holiness of life.

The saintly Pontiff then described the nature of canon law, indicating its organic development from God’s first covenant with His holy people. He recalled “the distant patrimony of law contained in the books of the Old and New Testament from which is derived the whole juridical-legislative tradition of the Church, as from its first source.”3 In particular, he reminded the Church how Christ Himself, in the Sermon on the Mount, declared that he had not come to abolish the law but to bring it to completion, teaching us that it is, in fact, the discipline of the law which opens the way to freedom in loving God and our neighbor.4 He observed: “Thus the writings of the New Testament enable us to understand even better the importance of discipline and make us see better how it is more closely connected with the saving character of the evangelical message itself.”5

The labors of Pope Saint John Paul II have borne remarkable fruit for the restoration of the good order of ecclesial life which is the irreplaceable condition for the growth in holiness of life. As a canonist, I note, in various parts of the ecclesial world, more and more initiatives, perhaps small but nonetheless strong, to foster the knowledge and practice of the Church’s discipline, in accord with the true post-Conciliar reform, that is, in continuity with the perennial discipline of the Church.

Today, we are sadly witnessing a return to the turmoil of the post-Conciliar period. In the past few years, law and even doctrine itself have been repeatedly called into question as a deterrent to the effective pastoral care of the faithful. Much of the turmoil is associated with a certain populist rhetoric about the Church, including her discipline.

New canonical legislation has also been promulgated which is clearly outside of the canonical tradition and, in a confused manner, calls into question that tradition as it has faithfully served the truth of the faith with love. I refer, for example, to legislative acts touching upon the delicate process of the declaration of nullity of marriage which, in turn, touches upon the very foundation of our life in the Church and in society: marriage and the family.

Given the situation in which the Church finds herself, it seems especially important that we be able to give an account of the irreplaceable service of the law in the Church, as also in society. It is especially important that we be able to recognize and correct rhetoric which is confusing and even leading into error a good number of the faithful.

To that end, I address the essential and irreplaceable relationship of doctrine and law with the pastoral life of the Church, that is, with the daily reality of Christian living. First, I will address the pervasive populist rhetoric about the Church and her institutions. Then, I will present a key teaching in the matter, namely the address to the Roman Rota of Pope Saint John Paul II on January 18, 1990.

Populist Rhetoric Regarding the Church

Over the past few years, certain words, for example, “pastoral,” “mercy,” “listening,” “discernment,” “accompaniment,” and “integration” have been applied to the Church in a kind of magical way, that is, without clear definition but as the slogans of an ideology replacing what is irreplaceable for us: the constant doctrine and discipline of the Church.

Some of the words, like “pastoral,” “mercy,” “listening,” and “discernment” have a place in the doctrinal and disciplinary tradition of the Church, but they are now being used with a new meaning and without reference to the Tradition. For instance, pastoral care is now regularly contrasted with concern for the doctrine, which must be its foundation. The concern for doctrine and discipline is characterized as pharisaical, as wishing to respond coldly or even violently to the faithful who find themselves in an irregular situation morally and canonically. In this errant view, mercy is opposed to justice, listening is opposed to teaching, and discernment is opposed to judgment.

Other words are secular in origin, for example, “accompaniment” and “integration,” and are used without grounding them in the truth of the faith or in the objective reality of our life in the Church. For instance, integration is divorced from communion which is the only foundation of participation in the life of Christ in the Church.

These terms are frequently used in a worldly or political sense, guided by a view of nature and reality which is constantly changing. The perspective of eternal life is eclipsed in favor of a kind of popular view of the Church in which all should feel “at home,” even if their daily living is an open contradiction to the truth and love of Christ. In any case, the use of any of these terms must be firmly grounded in the truth, together with its traditional expression of our incorporation into Christ’s Mystical Body by one faith, one sacramental life, and one discipline or governance.

The matter is complicated because the rhetoric is often attached to language used by Pope Francis in a colloquial manner, whether during interviews given on airplanes or to news outlets, or in spontaneous remarks to various groups. Such being the case, when one places the terms in question within the proper context of the teaching and practice of the Church, he may be accused of speaking against the Holy Father. As a result, one is tempted to remain silent or to try to explain doctrinally a language which confuses or even contradicts doctrine.

The way in which I have come to understand the duty to correct a populist rhetoric about the Church is to distinguish, as the Church has always done, the words of the man who is Pope from the words of the Pope as Vicar of Christ. In the Middle Ages, the Church spoke of the two bodies of the Pope: the body of the man and the body of the Vicar of Christ. In fact, the traditional Papal vesture, especially the red mozzetta with the stole depicting the Apostles Saints Peter and Paul, visibly represents the true body of the Vicar of Christ when he is setting forth the teaching of the Church.

Pope Francis has chosen to speak often in his first body, the body of the man who is Pope. In fact, even in documents which, in the past, have represented more solemn teaching, he states clearly that he is not offering magisterial teaching but his own thinking. But those who are accustomed to a different manner of Papal speaking want to make his every statement somehow part of the Magisterium. To do so is contrary to reason and to what the Church has always understood.

Making the distinction between the two types of discourse of the Roman Pontiff is, in no way, disrespectful of the Petrine office. Much less, does it constitute enmity of Pope Francis. In fact, on the contrary, it shows ultimate respect for the Petrine office and for the man to whom Our Lord has entrusted it. Without the distinction, one would easily lose respect for the Papacy or be led to think that, if he does not agree with the personal opinions of the man who is the Roman Pontiff, then he must break communion with the Church.

In any case, the more that such rhetoric is used without a corrective, that is, without relating the language to the constant teaching and practice of the Church, the more confusion enters into the life of the Church. Canonists have a particular responsibility to make clear what the doctrine and corresponding discipline of the Church is. For that reason, in particular, I judged it important to clarify the purpose of Canon Law.

The Intrinsic Connection between Canonical Discipline and Pastoral Practice

In his 1990 Address to the Roman Rota (the Pope’s ordinary court of appeal), Pope Saint John Paul II describes theinseparability of sound pastoral practice and canonical discipline:

The juridical and the pastoral dimensions are united inseparably in the Church, pilgrim on this earth. Above all, they are in harmony because of their common goal – the salvation of souls. But there is more. In effect, juridical-canonical activity is pastoral by its very nature. It constitutes a special participation in the mission of Christ, the shepherd (pastore), and consists in bringing into reality the order of intra-ecclesial justice willed by Christ himself. Pastoral work, in its turn, while extending far beyond juridical aspects alone, always includes a dimension of justice. In fact, it would be impossible to lead souls toward the kingdom of heaven without that minimum of love and prudence that is found in the commitment to seeing to it that the law and the rights of all in the Church are observed faithfully.6

As Pope John Paul II makes clear, it is impossible to speak of exercising the virtue of love within the Church, if we do not practice the virtue of justice which is the minimum required for a relationship of love.

The saintly Pontiff then confronts directly the pronounced tendency at the time, which has strongly returned in our time, to put in opposition pastoral concerns and juridical or disciplinary requirements. He underlines the insidious nature of such an opposition for the life of the Church:

It follows from this that any opposition between the pastoral and the juridical dimensions is deceptive. It is not true that, to be more pastoral, the law should become less juridical. Surely, the very many expressions of that flexibility that have always marked canon law, precisely for pastoral reasons, must be kept in mind and applied. But the demands of justice must be respected also; they may be superseded because of that flexibility, but never denied. In the Church, true justice, enlivened by charity and tempered by equity, always merits the descriptive adjective pastoral. There can be no exercise of pastoral charity that does not take account, first of all, of pastoral justice.7

The clear instruction of Pope Saint John Paul II is most timely in the present growing crisis regarding Church discipline. It expresses what has been the constant teaching and practice of the Church regarding mercy and justice, pastoral care and disciplinary integrity.

In Service of Justice in Love

It is my hope that this small reflection is of some assistance to you in understanding the actual state of canon law in the Church. In a time of crisis, both within the Church and in civil society, it is essential that our service of justice be firmly rooted in the truth of our life in Christ in the Church, Who is the Good Shepherd teaching, sanctifying, and disciplining us in the Church. There is, therefore, no aspect of the perennial discipline of the Church which can be overlooked or even contradicted without compromising the integrity of the pastoral care exercised in the person of Christ, Head and Shepherd of the flock in every time and place.

Through the merits of Christ the Judge of the Living and of the Dead and through the intercession of the Blessed Virgin Mary, His Mother and the Mirror of His Justice, may each of us remain faithful and steadfast in serving the justice which is the minimal but irreplaceable condition of the love of God and of our neighbor.

His Eminence Raymond Leo Cardinal Burke was Prefect of the Apostolic Signatura, the highest court in the Church, for six years. He has written extensively on canon law, the family, and the Eucharist.

See Canon Law Society of America, Code of Canon Law: Latin-English Edition, New English Translation, Washington, DC: Canon Law Society of America, 1998, p. xxvii. [Hereafter, CCL-1983].

CCL-1983, p. xxviii.

CCL-1983, p. xxix.

Cf. Mt 5:17–20.

CCL-1983, p. xxix.

Papal Allocutions to the Roman Rota 1939-2011, ed. William H. Woestman (Ottawa: Faculty of Canon Law, Saint Paul University, 2011), pp. 210–211, no. 4. [Hereafter, Allocutions].

Allocutions, p. 211, no. 4.