A Christian Consideration of Critical Theory

An interview with Carl R. Trueman by Carl E. Olson

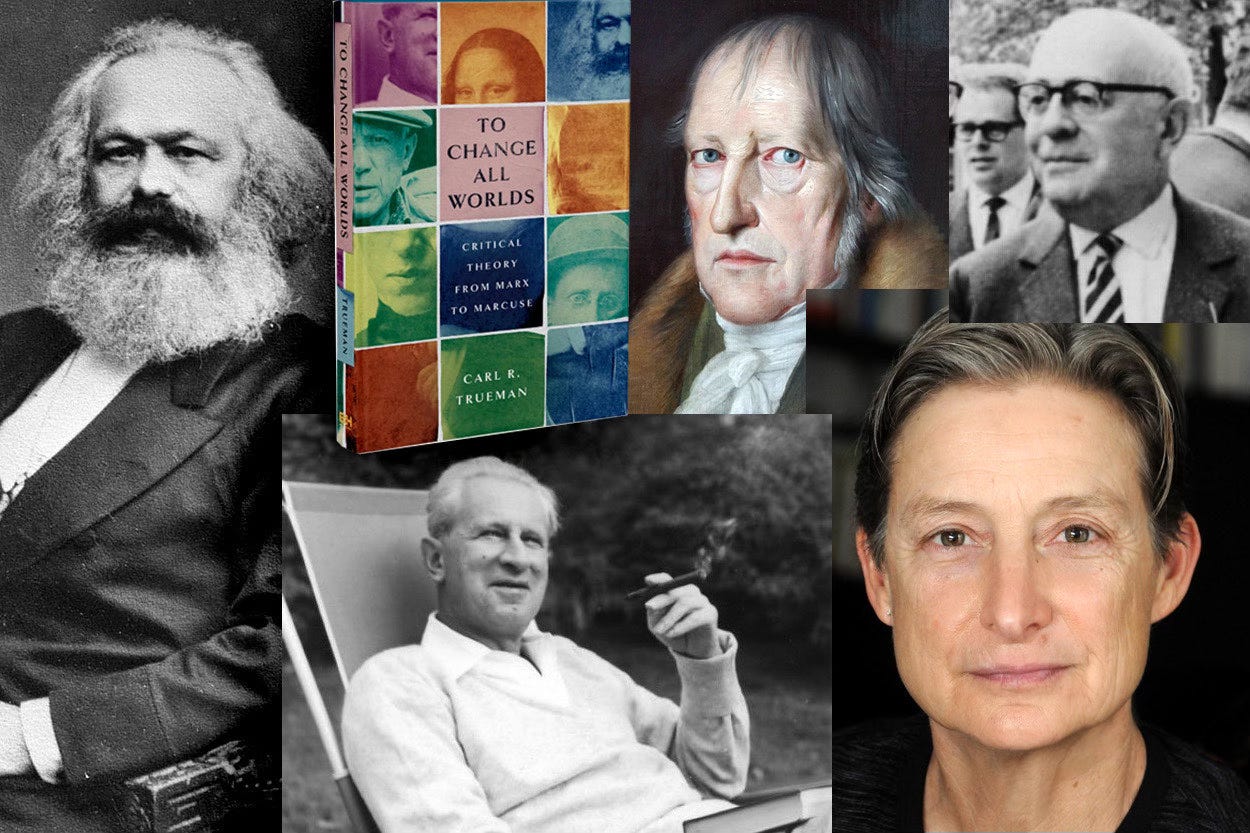

In Carl R. Trueman’s most recent book, titled To Change All Worlds: Critical Theory From Marx to Marcuse (B&H Academic, 2024), he hones in on the much-discussed but not always well-understood history, foundations, and goals of critical theory. In doing so, Trueman avoids polemics and hyperbole; rather than looking to argue, he seeks to understand. Charles J. Chaput, OFM Cap., in endorsing the book as “an essential read,” likens Trueman’s work to that of C.S. Lewis and says this book “is a brilliant exploration of critical theory and its impact on the central question we now face as a society: Who and what is a human being?”

I recently corresponded with Dr. Trueman about the book.

WWNN: What is critical theory, in a nutshell?

Carl R. Trueman: It is hard to give a concise answer because the term “critical theory” embraces a variety of approaches to the analysis of culture. Some of these are Marxist in origin, such as those associated with the Frankfurt School, whilst others owe more to post-structuralism of a figure such as Michel Foucault.

What all share in common is the intention of destabilizing the status quo, of unmasking the power games and manipulations that lie behind the kind of morality, social practices, and sociological and political categories upon which it depends.

WWNN: You assert at the start of this new book that the importance of critical theory is that it is “wrestling with the question of what, if anything, it means to be human...” How does it address basic anthropological questions? And what is lacking in that engagement?

Trueman: One important insight of critical theorists in general is that what it has meant to be human has changed over time and between cultures.

This impulse comes initially from the appropriation of Hegel, and the earlier Hegelian writings of Marx. With critical theorists, this then alters the question from “What is man?” to “Who benefits from defining ‘man’ in this way?” That is a legitimate question, as we know that, for example, a normative understanding of human nature as white was used in the past to justify race-based slavery.

The problem is that this approach also tends to assume that categories such as “human nature” can be reduced to manipulative power relations. That is antithetical to Christian claims about human beings as those made in the image of God as an ontological reality.

WWNN: If critical theory is aimed at questions such as, “What is man?”, why is it now known primarily as a neo-Marxist form of political radicalism, wokeism, and reverse racism?

Trueman: As mentioned in the previous answer, critical theory makes the anthropological question an ineradicably political one. Hence, it manifests itself in all areas of the modern world where questions of the manipulative use of social and cultural categories (race, gender, sexuality, and so forth) are important to political discourse.

WWNN: The Frankfurt School has, it seems, become a sort of mythical and contentious topic for some when it comes to the origins of critical theory. What are the key facts, especially relating to the mostly privileged and Jewish background of the Frankfurt project?

Trueman: The key figures in the early Frankfurt School, such as Max Horkheimer, Theodor Adorno, and Herbert Marcuse, were from very comfortable Jewish backgrounds. That has at least a twofold significance.

First, they were very well-educated and thus deeply read in the Western philosophical tradition. Second, they were nonetheless outsiders in a country that was moving rapidly into the nightmare of Nazism. They were thus both insiders in one sense but also outsiders.

It also meant they were preoccupied with the specific questions of why significant numbers of the working class in Germany supported the nationalist parties rather than the Communists, and how and why the most culturally sophisticated nation on earth was descending into barbarism.

That latter question was not a Marxist monopoly; Thomas Mann addresses it allegorically in his Doctor Faustus. The Frankfurt School found answers by appropriating elements of Hegel and Freud for a revision of the Marxist project that focused not primarily on the economic movement of capital but on notions of consciousness.

They thus focused on analyzing how societies create and manipulate cultural consciousness as a means of understanding why, for example, the working classes freely voted for Hitler and against their own economic interests. One famous aspect of this was Adorno and Horkheimer’s notion of the culture industry, a term they used for the various systems societies use to shape how people think about the world around them.

WWNN: The Frankfurt School, you write, “has insightfully framed questions about the human condition and has legitimate concerns about objectifying persons, [but] it does not offer compelling answers to the anthropological questions it raises.” What are some of the questions it got right? And how did it get the answer wrong?

Trueman: The Frankfurt School rightly saw how modern society tends to treat people as things. Mass bureaucracies do this. Employers who see their employees as interchangeable with each other do this. More subtly, the ethics and practices of the sexual revolution that turned sex into a self-directed recreation by making sexual partners into nothing more than instruments for personal satisfaction do this.

And who of us likes being treated in such a way? We are made to treat others—and to be treated by others—as unique persons, as subjects, not objects. On this point, the Frankfurt School shared the same philosophical concerns that we find in Kant and his successors. As Marxists, they see the culprit as capitalism, but from the vantage point of the twenty-first century, we can see that Marxist-based alternatives proved even worse in this regard.

The real problem, as Christians know, does not ultimately lie in some cultural or economic system but rather in the human heart. As fallen creatures, we inevitably tend to treat others as things that exist for our convenience. The answer to that is Christ and his grace, not economic or political revolution.

WWNN: Much of your book, of course, explains how we got to where we are now, in 2025. Can you summarize a few of the essential paths or trajectories involved in that philosophical and political journey?

Trueman: Our modern condition is genealogically complicated, but there are few key issues that lie at its heart.

First, there is the move to prioritize inner feelings as definitive of who we are as human beings. We see that starting in the late medieval period and accelerating with figures such as Descartes and Rousseau in subsequent centuries.

Second, as human nature is psychologized, politics shifts from economic to psychological concerns. The early Frankfurt School represents a transitional movement on this point, still committed to the basic Marxist notion of economic capitalism as the problem, but moving attention to the critique of ideas of a culture’s intuitive ways of thinking.

Today, critical theory is largely detached from old-style Marxist thinking about economic class. I would also add that the emergence in the nineteenth century of the rebel or transgressor as a cultural hero has played a significant role too, making perpetual iconoclasm, rather than the transmission of tradition, the vocation of our cultural officer class–artists, educators, politicians, etc.

Significantly, that resonates with a world marked by technological innovation. Thus, the ideology of culture and the ethos of the technological world are symbiotic in creating a world of flux.

WWNN: As you have discussed in detail in previous works, the sexual revolution is, at the core, about what it means to be human. How did critical theory inform the sexual revolution decades ago? And how does it continue today?

Trueman: The early Frankfurt School appropriated Freud’s insight that sexual codes are constitutive of society but then historicized that point with a Marxist twist, arguing that specific sexual codes supported specific forms of society and the particular forms of oppression upon which those societies depended.

That opened the way for placing sexual codes at the center of politics: to overthrow capitalism, one had to shatter the sexual codes (monogamous, heterosexual marriages as the foundation of nuclear families) upon which capitalism depended. The economic underpinnings of this may now have been sloughed off, but the idea that sexual codes are oppressive and need to be shattered has remained a staple of modern politics.

WWNN: One of many strong qualities of your book is that you take seriously the concerns, rhetoric, and criticisms of the philosophers and theorists you discuss and analyze. Can you talk about your approach and goals in that regard? What sort of mistakes can Christians make in being dismissive or relentlessly polemical when engaging with critical theory?

Trueman: First, I am an intellectual historian, and therefore my primary task with any texts, ideas, or thinkers is to explicate them in historical context.

For me, that is perhaps the most interesting aspect of such work: Can I explain these thinkers in a manner that they themselves would recognize as fair and balanced?

Second, rare is the thinker or idea that is completely wrong at every point. In the book, I use the analogy of ancient heresies. Arius, for example, had a doctrine of God that was ultimately inconsistent with scriptural teaching. But he nonetheless asked an important question: What is the relationship between the Father and the Son? To move to the correct answer on that point requires both understanding why the question is important and why his own answers were wrong.

It is similar with critical theory, which is best approached by Christians as asking good questions that require careful answers, and as providing answers whose weaknesses and problems enable us to find more adequate ones.

To attack (or embrace) critical theory without properly understanding it is disastrous for numerous reasons, perhaps most obviously because such wrongheaded engagement cuts us off from offering a better alternative.

WWNN: In the conclusion, you reflect on what Christians need to do in refuting critical theory. What are some of the key points you outline and prescribe?

Trueman: Read the sources in context. Understanding what a text means or is doing in context is a necessary precondition to critique. Acknowledge the legitimacy of the questions it asks, but do not be intimidated by that.

When it comes to the central concerns of what it means to be human, how humans should treat each other, and why they fail to do so, Christianity has better answers. Demonstrating the legitimacy of critical theory’s questions has to be accompanied with showing the inadequacy of its proposals and the offering of more adequate alternatives.

Carl E. Olson is editor of Catholic World Report and Ignatius Insight. He is the author of Did Jesus Really Rise from the Dead?, Will Catholics Be “Left Behind”?, co-editor/contributor to Called To Be the Children of God, and author of the “Catholicism” and “Priest Prophet King” Study Guides for Bishop Robert Barron’s Word on Fire. His recent books on Lent and Advent—Praying the Our Father in Lent and Prepare the Way of the Lord—are published by Catholic Truth Society. Follow him on Twitter @carleolson.